Aquinas on Why the Incarnation of Jesus Christ Matters

Christians believe that among the most significant events in history was the Incarnation. The second person of the Trinity, the Son of God, took the form of a human and came to earth. Philippians 2:7 says:

"rather, he made himself nothing by taking the very nature of a servant, being made in human likeness."

And John 1:14 says:

"The Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us."

These two verses are two of the Bible's most direct statements about the Incarnation. But its importance is implied, and Christian theologians throughout history have highlighted the importance of it.

I honestly haven't reflected on the Incarnation as much as I should. The churches in which I was raised believed in the Incarnation, but it wasn't a teaching that was dwelled upon. But I know that for many Christians throughout the centuries, the Incarnation has been one of the chief cornerstones of Christian devotion.

So when I was reading Brian Davies' book on Thomas Aquinas, Aquinas, and came across Davies' summary of why Aquinas thought the Incarnation of Jesus was so important, I stopped and read it carefully.

It's something I thought I would share with you, especially since many of you probably share my experience and haven't spent much time reflecting on the significance of the Trinity.

"Yet, why should it be thought that the Incarnation is of any special significance to us? What can we draw from the teaching that Christ is God? According to Aquinas, 'when one earnestly and devoutly weighs the mysteries of the Incarnation, one will find so great a depth of wisdom that it exceeds human knowledge' (SC IV, 54). He does, however, think it possible to give some account of the importance of the Incarnation. His basic position is that, by virtue of God incarnate, we are united to God as to a loving friend. One might naturally suppose that the gulf between people and God is too great for them to come together in any way....

[...]

"I love Smokey [Davies' cat]. I also love good literature, good meals, good wine, good holidays, and a good night's sleep. But I would never say that I am in love with such things. For I take being in love to imply equality (cf. ST 2a2ae,25,3). We naturally speak of people as being in love with each other, and of them as giving themselves in love to each other. We do not naturally speak of people as being in love with they cats, or with books, meals, and so on. When we are thinking of mature, adult love (the sort of thing that poets like John Donne write about so effectively), we have in mind a relation between equals. And this, Aquinas believes, is something that could never be thought to obtain between God and creatures simply on the basis of what can be said of God as we reflect on the fact that God is the Creator. We might, he agrees, speak of God as being good to creatures insofar as he gives them what is good for them. And, since he does this, we might even say that God loves creatures, just as we might say that I love Smokey since I feed him so regularly. But we have no warrant for any suggestion to the effect that God might deem creatures to be equal to himself. We have no warrant for suggesting that God might be in love with a creature as people can be in love with each other....

"But that, Aquinas holds, is precisely what we can suppose in the light of the Incarnation. For he takes this to show that God loves people as he loves himself. Aquinas relishes passages in the New Testament such as the one in which Jesus says to his disciples 'As the Father has loved me, so have I loved you' (John 15:9). And, since he believes that Jesus is God the Son, he concludes that people are loved by God, not just creatures, but as what God loves insofar as he loves himself. Or, to put it another way, Aquinas teaches that people can share in what the Trinity is. 'The human mind and will,' he says, 'could never imagine, understand, or ask that God become man, and that man become God and a sharer in the divine nature. But he has done this in us by his power, and it was accomplished in the Incarnation of his Son' (CE 3,5)...." (pp. 147-49)

I know that some of this language is strange, even alarming ("...that God might deem creatures to be equal to himself"), but I think that a moment's reflection will help us see what Aquinas is getting at.

Aquinas understands God as so transcendent, so beyond the creation and even what humans can imagine, that there isn't much we can know about him without His revelation to us. And this transcendence, this utter difference from what we experience in this world, makes it difficult to see how we can relate to God at all, much less as children who love the Father and are loved by the Father.

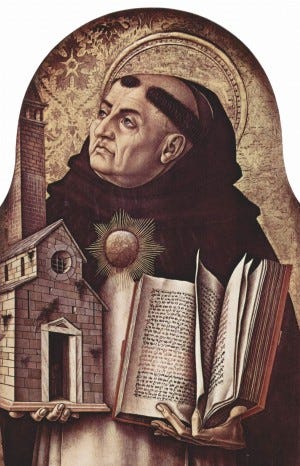

Source: Wikimedia

This is the point of Davies' distinction between loving something and being in love with something. We understand this. Our most intimate and personal relationships are not with objects lower than us. You don't have intimacy and a personal relationship with your lawn tools, your house, or even your pets. And though we use the language metaphorically, your dog is not truly your best friend. True friendship is reserved for people on our level, for those we can relate to.

But we can't relate to God as the transcendent, distant God. (Though Aquinas doesn't address the possibility of intimacy with God in the Old Testament, I think we can say that the intimacy was a foreshadowing of the greater intimacy after the Incarnation.)

But when Jesus came in the flesh, the level of intimacy we have with other humans –– our fathers and friends –– can now be fully had with God-in-the-flesh. Jesus, after all, said in John 15:15:

I no longer call you servants, because a servant does not know his master's business. Instead, I have called you friends, for everything that I learned from my Father I have made known to you.

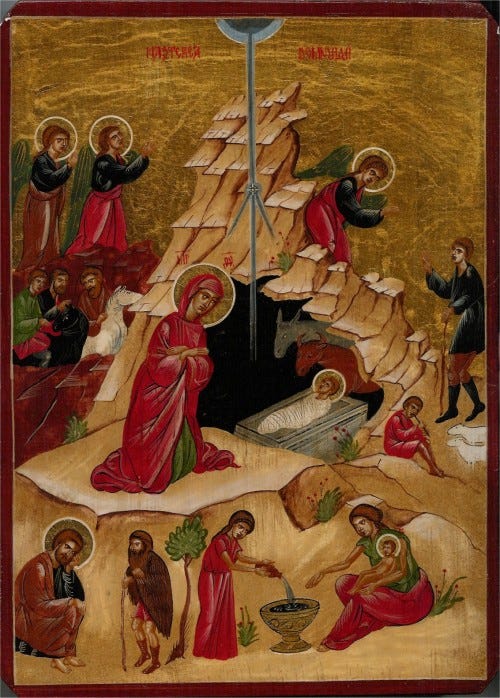

Then Incarnation, then, deepens the devotion that we can have to God because it enables our love for God to become the intimate love that we find possible for humans that are relatable. And, perhaps more importantly, God–in–the–flesh fleshes out for us what it means for God to love us sacrificially.

I think this is confirmed by the usual experience of reading the Gospels. It's not that the rest of the Bible doesn't show us a glorious and loving God whom we trust, love, and follow. But reading the Gospels (for me, at least) leads to a deeper love of God and a deeper understanding of the love of God for his people.

And the possibility of this experience is one of the reasons that the Incarnation is momentously important.