Francis Schaeffer and the Bible's Human Factor: Why It's Not a Secondary Concern

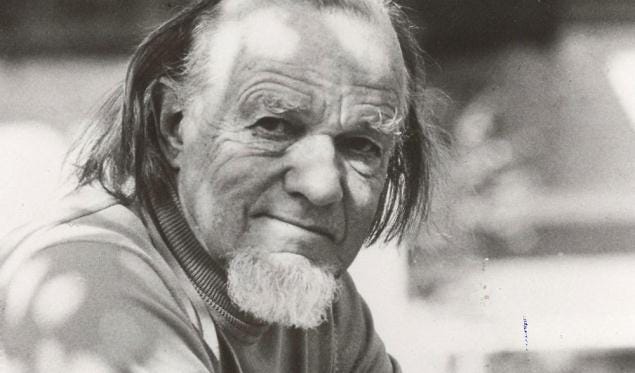

When I was in high school (I went to a Presbytian Church of America high school), my Bible teacher talked about Francis Schaeffer a few times. I had never heard of him before. But in college I read a few of his books. I also read a couple of biographies about him. He was an amazing missionary and minister, and he served as an example of a Christian minister engaging culture and intellectuals, especially college students. And his book, True Spirituality: How to Live for Jesus Moment by Moment, remains one of the most influential books in my life.

So when I saw William Edgar's book, Schaeffer on the Christian Life: Countercultural Spirituality, part of the "Theologians on the Christian Life" series, I ordered it and read it. The narrative of Schaeffer's life and ministry was interesting. The rest of the book, though, didn't hold my attention the way that another book in that series, Fred Sander's Wesley on the Christian Life: The Heart Renewed in Love, did. Edgar did a good job writing the book; I don't think he's to blame for me being underwhelmed by the book. Perhaps it's just that I am more familiar with Schaeffer's writings and viewpoints than I am Wesley's writings and viewpoints.

I did take issue, though, with some of Schaeffer's views. One in particular stood out to me as dangerously false. It was Schaeffer's view of inspiration and how that affects the ways that the Bible should be used.

Edgar writes:

"Although Schaeffer did not explore the science of biblical hermenutics in any depth, he did believe in the analogy of Scripture as taught by the Reformers. That is, one portion of Scripture can explain another, because the Bible is one book. Thus, in his Basic Bible Studies he declares that 'because one of the wonderful things about the Bible is its unity, Bible study without keeping this unity in mind is a real loss." Both in his preaching and in extended scripturally based studies, Schaeffer usese a thematic approach rather than a biblical-theological approach. That is, he draws on many portions of Scripture, using something like a cumulative effect, in order to derive a doctrine or make a point, rather than taking a specific text both in its original horizon and then in its relation to the historical unfolding of redemptive history, culminating in Christ. Such a 'proof-texting method,' as the older approach is sometimes known, is not wrong, since the Bible does have a fundamental unity within its diversity. Indeed, Schaeffer was thoroughly committed to the unity of the Scriptures. In his personal devotions he read something like four chapters of the Old Testament and one chapter from the New Testament every day. but such a focus on the unity of the Bible may deprive one of the richness of a particular portion's literary structure, or of the place of a revelation within a specific season in the flow of redemptive history. It may also minimize the human side of biblical revelation. While Schaeffer certainly recognized the human factor in the Bible, it was not his primary interest." (85-96; emphasis mine)

If Edgar's summary of Schaeffer's view is right, then I think that Schaeffer was mistaken. The unity and divine inspiration of the Bible are no reason to prooftext or to treat the human factor in the Bible as a "secondary concern".

I believe that the Bible has a fundamental unity. If the Bible is God's Word, then it follows that the message from God wouldn't contradict itself or have any falsehoods. But this point gets ushered into damaging usage by Schaeffer. Yes, the message of the Scriptures form a unity, and we would do it a great disservice to ignore that unity. But this unity doesn't give us license to ignore the richness and depth of passages in the Bible.

The unity of the Bible should drive us to understand the intercanonical connections and themes. It should motivate us to understand how segments of the Old Testament fit into our understanding of God's work in the world. But it shouldn't motivate reckless prooftexting. I trust that Schaeffer was a careful exegete, but prooftexting is not healthy. Of all the terrible Bible discussions I've sat through, most have involved prooftexting.

What's the problem with prooftexting if you are careful not to grossly misinterpret the verse? It often leads to missing the depth and richness of God's revelation to us. As Edgar said in the quoted text, Schaeffer's method of Bible study led to the loss of this richness. But the richness lost isn't a garnishment of the verses being used. It is lost meaning. When we sacrifice the depth and richness of a text through prooftexting, we are sacrificing the depth and richness of the divine revelation to us. And there are few things that the church needs more than the great riches of God's revelation to us.

While Edgar implies that Schaeffer's recognition of the divinity of the text makes Schaeffer-style prooftexting okay, I disagree. It is the divine inspiration of the text itself that makes Schaeffer-style prooftexting dangerous and misguided. The prooftexting leads to the loss of riches and depth that God wanted us to see in the Scriptures.

All of this is obvious in the last sentence of the quote from Edgar's book. Edgar writes, "While Schaeffer certainly recognized the human factor in the Bible, it was not his primary interest." But how can Schaeffer separate the human factor from the divine factor? Is the human factor just extraneous? Would the Bible be improved if we just removed all the human bits and focus on the divine stuff? Is Paul passionate temperment, especially regarding the purity of the gospel message, a part of the human factor that can be treated as a secondary concern? I think we lose something important if we bracket out Paul's zeal as a human factor that only needs to be our secondary concern.

The doctrine of inspiration teaches that God revealed Himself through the human factor. You cannot merely bracket out the human factors and ignore them any more than we can treat Jesus's humanity as a secondary issue. I don't trust any theologian, no matter how intelligent or well-read or spiritually wise, to filter out the "human factors" in the Bible so that we can treat them as a secondary or tertiary concern. And, even if someone could, if God was revealing himself through those very human factors, then we would be missing something.

It is the divine nature of the Bible--in this instance, the divine use of the human factors in the Bible to teach us about God--that invalidate Schaeffer's view. Schaeffer was used by God in great ways, and I respect and honor that. But prooftexting and the view of the Scriptures that encourages it needs to dissappear from our churches. What we need is a generation of Christians who will study their Bibles closely and see the riches and depth of God's Word.